This article was originally published in Rethinking65

Nearly one-third (30%) of the financial advisors who earned their CFP credentials during 2022 were women, progress worth celebrating. Women are joining the ranks at a faster pace although they still comprise just 23.6% of the total CFP count — a figure that hasn’t budged in a decade.

Kate Healy, managing director of the CFP Board Center for Financial Planning, isn’t hung up on that stagnant statistic; she’s glad more women and men are becoming CFP professionals and says the big denominator (95,137 as of December 31) makes it difficult to move the needle.

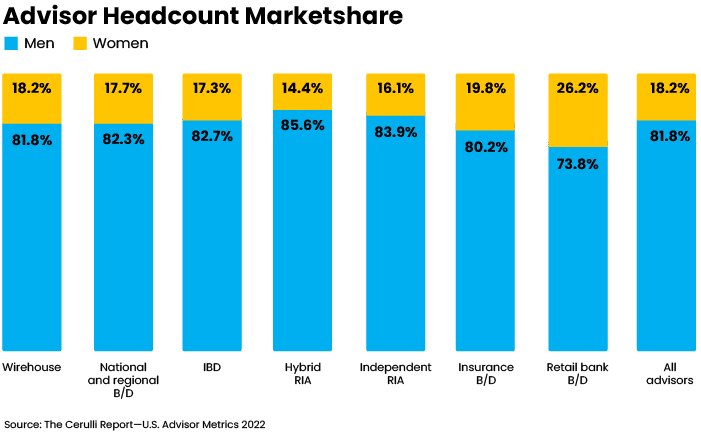

But by quoting the 23.6% and Cerulli Associates’ numbers for female advisors across the industry (18.2%) and in the independent RIA channel (16.1%), “We sometimes do ourselves a disservice,” says Healy. “We scare women away by saying, ‘This is a really, really male dominated profession.’”

Retaining women is an even bigger issue than attracting them to the profession, many industry leaders tell Rethinking65. Research from Carson Group’s recently published “2022 State of Women in Wealth Management Report” also provides some insight on this.

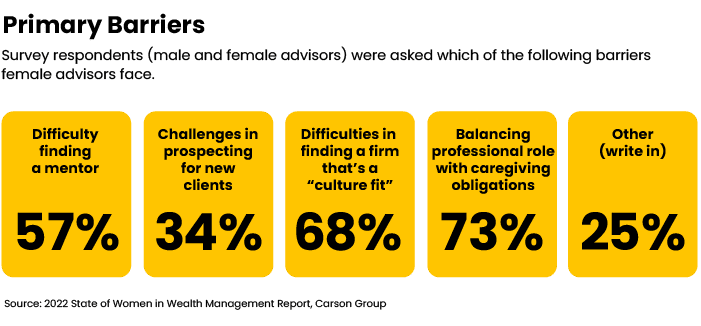

The survey asked male and female advisors what barriers female advisors face and provided four choices plus a write-in option. Their responses: difficulty finding a mentor (56.9%), challenges prospecting for new clients (33.5%), difficulties finding a firm that’s a “culture fit” (69.8%), balancing professional role with caregiving obligations (72.7%) and other (24.5%).

Alone in a crowd

“Once you get in, you realize anywhere from 70% to 80% of your peers don’t look like you and it’s difficult to find and connect with peers that understand your story, your journey and the type of advisor or financial planner that you want to become,” says Shannon McLay, CEO and founder of The Financial Gym, a national personal financial services company.

Marguerita Cheng, CEO of Blue Ocean Global Wealth, an investment advisory firm in Gaithersburg, Md., was also unprepared for that when she entered the advisory profession in 1999 after working as an analyst and editor at a securities firm in Tokyo.

As a new advisor back home in the U.S., “I didn’t see anybody [else] who was ethnically diverse, racially diverse, let alone a mom … I felt very, very alone,” she says. “I think that sometimes people underestimated me. And sometimes I would underestimate myself.”

“I don’t think people were overtly racist, sexist … It’s just they were genuinely confused: ‘How can you do this? We’ve never seen anybody do this,’” says Cheng.

Multiple gaps

The shortage of women leaders to serve as role models and mentors is problematic, says Bridget Grimes, president of WealthChoice LLC, a San Diego-based wealth advisory firm for female lawyers and female executives, and co-founder of the Equita Financial Network for female advisors.

In addition, “roles in the industry don’t provide flexibility needed for women with families, or women who want some sort of balance in their life. Pay disparity continues to be an issue. And at many firms, the model of focusing on business development and revenue over serving clients doesn’t resonate with a lot of women,” she says.

It’s hard to find data on women leaving. But CFP professionals have an overall retention rate of 97% so they aren’t leaving the industry as much as they are changing firms or business models, says Healy of the Center for Financial Planning. Women often move on to start their own firms or join firms where they can find better work-life balance, support the type of clients they wish to support, and be heard, she says. Grimes and McLay started out at wirehouses; Grimes later worked at a male-led RIA firm. Cheng began advising at an independent broker-dealer firm.

Myth-busting and new paths

Making it easier and more appealing for women to enter, grow and stay in the advisory profession includes dispelling a lot of the myths about what the industry and being an advisor are really about.

For many women, “the selling piece is scary,” says Healy. The misperception that being a financial advisor is just about selling, and specifically commission-based selling, has created concern that they can’t earn a good living right away, she says.

She can relate: “I’m a failed financial advisor because I hated the selling part … Now, I understand what it is and it’s a whole different thing that I have much more confidence about being able to do than when I was 28.”

Furthermore, people who didn’t set out to be advisors often build their confidence after they get into the financial services business, “see what it’s like, and begin to understand the relationship aspect of what financial planning and being a CFP is really about,” says Healy.

Building confidence only goes so far. Firms also have to be committed to “creating a pathway,” says Healy, for women who come in the door as advisors and for those who don’t.

Women make up 46% of the RIA industry, with many serving in administrative or operational roles including client services, trading, marketing and compliance, she says. As long as firms are supportive, she says, “there’s a very, very solid career path from being an operations professional or client service associate to becoming an advisor, if that’s what you want to do.”

Healy encourages firms and individuals to check out the CFP Board’s Guide to Financial Planning Career Paths, which explains different business models and how to get to the next level. She also encourages women to speak with advisors in various firms and roles and to listen to their stories of how they came into the profession.

Meanwhile, more firms are creating business development departments so new advisors, especially on the independent side, are “not necessarily tasked with bringing in clients right away,” says Healy. She thinks this structure will appeal more to some women.

Beyond initiatives

Grimes encourages the planning industry to borrow from the playbook of other industries that have begun to take some steps that are benefiting women professionals. For example, new salary-transparency data in tech is helping her female clients in technical roles see where they fall on the compensation scale, she says.

“If firms provide flexibility in roles, which allows women to have a family, to take time for family, to provide great work on their schedule, they are more likely to both attract and retain women,” she says. “If there is pay transparency, we can overcome the pay disparity issue, and if firms advance more women to leaderships roles so there are actually women who could serve as mentors, all of these could help with attraction and retention.”

She’s also like to revisit the role of advisors so that women can focus more on meaningful work and relationships with clients instead of being tied to the commonly used revenue-focused model. [Advisor Cary Carbonaro has written about the fee structure that works for her.]

“Having a network/community of women planners is also a critical piece,” says Grimes. “Women want and need relationships with others in similar roles. It provides support, encouragement, sharing, and can truly help women succeed.”

She and financial planner Katie Burke, founder of Method Financial Planning and co-founder of the Equita Financial Network, launched their own firms so they could have the flexibility they desired, “get paid what we were worth, and serve who we wanted the way we wanted,” says Grimes. “And very importantly, we could be as successful as we wanted and not be told we were ‘too ambitious.’”

“But this is an expensive and lonely endeavor,” she says, so she and Katie become each other’s support and community.” They then launched Equita to share their resources with other women advisors seeking an economically feasible way to stay in the industry on their own terms, says Grimes.

Life experience counts

“Retention is just as important as attracting female talent,” says Christine Vignola, a branch leader for Fidelity Investments in the New York City metro area.

Fidelity has a number of initiatives aimed at retention. Its Women’s Leadership Group helps like-minded women and men connect and build relationships, says Vignola, who has developed long-term friendships from being a member. The company’s 10 affinity groups (more than 45% of Fidelity’s associates belong) provide community, mentorships and development programs.

Fidelity’s six-month return-to-work program, Resume, for individuals who have taken an intentional career break for at least two years, provides access to work opportunities, readiness assessments, professional development, networking, and mentoring. In 2017, Vignola helped launch a division of Resume for the Fidelity Investor centers, with a focus on getting returners or career-changers on a path to becoming financial planners.

“While the program is open to anyone who has taken an intentional career break, most of the participants are women who stepped away from the workforce to raise children,” she says. “Through that work it became apparent that life experience, married with professional skills, are invaluable when connecting with clients.”

More mentoring efforts

Jacqueline (“JaQ”) Campbell, founder of Alexander Legacy Private Wealth Management, is in the process of creating Launch to Legacy, a program to recruit and retain women and minorities in wealth management. She was inspired to create a program because there are only a few programs specifically on a mission to advance women in the profession, she says, including Females and Finance.

Mentoring needn’t be formal nor a large time commitment to be worthwhile, says Cheng of Blue Ocean Global Wealth. She’s had women reach out to her through the CFP board, including other Asian women, and has met with some remotely.

One of her mentees had been doing business banking for more than a decade and wanted to earn her CFP certification; her boss said she didn’t need it and denied her request.

“I wrote out three sentences for her to say: ‘In my present role, I don’t necessarily need to have CFP certification. But it will help me serve the business clients in a more holistic manner. And by serving the clients better, they’ll be more loyal and do more business with the bank,’” says Cheng. “He paid for her to do CFP certification.”

Cultivating young talent

More advisors and firms are also working to boost industry awareness at a younger age.

“Recruiting women into financial planning roles has its challenges primarily because the pool of talent is so limited. Essentially, the entire industry is fishing in the same small pond,” says Vignola. “What we need to be doing collectively is expanding the pipeline of talent of young women into this industry.”

Fidelity is focusing on this through its work with Invest in Girls and Boundless, a Fidelity program that provides financial services career exploration opportunities for high school girls.

Vignola knows how important it is to engage with young women: She became interested in the stock market when her high school social studies teacher went off lesson plan and shared the financial pages of the Wall Street Journal to teach the class about it.

“I can still picture the long pages hanging over my desk. I was mesmerized seeing the company symbols and stock quotes,” she says.

As a teenager, Campbell participated in a high school co-op program that introduced high school students to careers in corporate America. Teaching financial literacy at a younger age can help attract more women to the industry, she says.

In addition, offering mentoring for young women and career changers is “always important as women are becoming more and more the breadwinners and holding the fiduciary and fiscal responsibilities for their families,” she says.

Campbell would like to see more colleges partner with financial planning practitioners to teach planning courses and offer a career-path option “given current demand for next-gen talent,” she says. She also favors making CFP and other credentials more affordable through scholarships and grants. The CFP Board awards two-thirds of its scholarships to women, it says.

To boost awareness of the profession on a widescale, national basis, the CFP Board is developing a “future workforce” program that it’ll initially aim at high school and undeclared college students, says Healy.

Making the industry ‘female friendly’

Cary Carbonaro, the director of Women & Wealth at ACM Wealth (the wealth planning team of Advisors Capital Management) and a CFP Board ambassador since 2014, has many ideas about how to help improve situations for female advisors and female clients.

“I want to make the industry female friendly for advisors and for clients,” she says. “I want to change the client experience to meet women where they are — and not try to take the current language of beating the benchmark (male) — and make it about being able to sleep at night or having financial freedom, whatever that looks like for her.”

“I want women to want to hire a financial advisor not in the middle of a crisis but just because they know it will enhance their lives or because they want to make smart decisions with money.”

“It is a really big goal, bigger than me, so it will take a village,” says Carbonaro. In 2017, she resurrected the women’s initiative at her previous firm, United Capital. Ever since, she’s been speaking regularly with like-minded female professionals about how the advisory business needs to change.

The CFP Board Women’s Initiative (WIN) turns 10 this year. But there is still a shortage of initiatives for women because “we are such a minority and women are just trying to do what they have to do to get through the day,” she says. “I think I was able to take the lead on this because I didn’t have children at home. If I did, I don’t think I would have been able to do all of this. No man is going to say we need this. It is an industry built by men for men.”

What must women do in order to help get more women to enter and stay in the industry? “Make them feel supported, zero tolerance to the bad behaviors from men. How about a defined career path, paying them what they are worth, putting them in lead roles, etc., etc. Not using AUM as a measuring stick,” says Carbonaro. “Make them safe and establish a community for them!”

Removing unconscious bias

As firms review their policies, it’s also important for them to remove any unconscious biases they may have from the recruiting or promotion angle, says Healy of the Center for Financial Planning. “It’s got to be part of their strategy; it can’t just be an afterthought,” she says. Both Napfa and the Financial Planning Association offer toolkits on this.

Acknowledging and addressing overt sexism — and creating and enforcing policies to prevent it — is also essential.

McLay of The Financial Gym recalls comments from her wirehouse days and says, “I think that any woman who has been through the industry in the last 20-plus years probably had similar stories to me.” One peer asked her how old she was and when she told him, he said, “Oh, you’re too old to be my mistress,” she says. “I had a client ask me what type of panties I wore.”

While hosting a women’s networking event at her Merrill Lynch office, a peer asked if she was hosting a Tupperware party. Although she laughed while relaying his comment to her attendees, “they said, ‘Are you going to report him to HR?’” she says. “I thought, ‘Who has Tupperware parties anymore?’ – that just kind of showed his age. But at that point, I’d been in the industry 20 years and I think it was just how desensitized I was.”

Such behaviors — and worse — persist because “there’s just not enough women in the room contributing to training programs and retention programs and having that voice,” says McLay. “There’s a lot of gaslighting. It’s a boys’ club and boys protect each other,” and the mistreated women often don’t say anything.

How male allies can help

For Campbell of Alexander Legacy, the most interesting finding in the Carson report is that “both men and women agreed 90% of the time that there is still much work to be done in our industry,” she says. Her firm is a member of the Carson Partners network but she did not work on the report.

Burt White, Carson Group’s chief strategy officer, says, “I think seeing just how little change there has been for women in our profession over the last 20 years was surprising and disappointing. It was reassuring to see that the men surveyed think that underrepresentation within the industry is a pressing problem. That’s a good start!”

So how can male advisors better support female advisors? Mentoring is key, says White.

“We know two things for sure: “There are too few women in the industry (and even fewer in leadership) and that women here want mentors.” he says. “That means the men who make up 80% of the industry need to step up and start mentoring more women.”

During Carson’s research interviews, female advisors shared inspiring stories about how male mentors had introduced them to important contacts, created smooth transitions for clients and taught them effective prospecting, he says.

Carson Group is looking into an internal mentorship program and plans to continue this research every year, says White. It also hosts yearlong study groups for women on different topics and collaborated to host the women-in-wealth-management initiative Excell REPRESENT.

Vignola says Fidelity’s Women’s Leadership Group has a committee called “Men as Allies,” which provides practical advice on how to be an advocate for women in the workplace.

Campbell adds that a culture of male allies should also include male clients. “Do business with women! Give us an opportunity,” she says. “I believe allies do more than ‘talk.’ They are willing to put their money where their mouth is and be a true supporter, by being a paying client!”